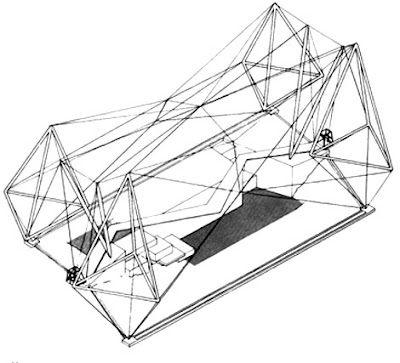

The aviary, undertaken with Lord Snowdon and Frank Newby (b. 1926), consisted of a wire mesh enclosure, cable-supported around four floating tetrahedral frames, below which was a walkway for observers. The cage was engineered by Newby, who became Price’s principal structural consultant. The theatrical impresario Joan Littlewood proposed the idea of the Fun Palace, which she described as a ‘laboratory of fun’ and a ‘university of the streets’, which was to be developed with Cedric Price. It was to be a recreational and educational facility engaging and stimulating its visitors through providing topical and thus ever-changing spaces, places and opportunities. The Fun Palace was not intended for passive, Disneyland-style entertainment; the Price response was a design consisting of towers, gantry cranes, movable floors, walls and ceilings, suspended auditoria and walkways, vapour barriers and horizontal and vertical blinds. All these components were designed to accept constant change. Price began to investigate new ways of relating temporality and form, asserting that any built environment would become inhibiting, restrictive and ultimately obsolete unless its inhabitants could accommodate the indeterminate and the impermanent. The Fun Palace was the first of many buildings and projects supporting Price’s idea that architecture should not determine human behaviour but rather enable possibility.

Price’s vision of education, educational settings and their potential for rehabilitating a declining area went far beyond the conventional university campus. He conceived of his Potteries Thinkbelt (1963) not as a building but as a network of flexible and flexing facilities linked by, and taking full advantage of, the underused railway system of surplus lines, sidings and derelict land, at a chosen site in the ‘Potteries’ in his native Staffordshire. Price’s use of a railway system was intended to exploit existing resources and to assert the significance of communications but also to polemicize against thoughtless conventionality. The railway system monopolized the attention of critics, some of whom missed the Potteries Thinkbelt’s larger purpose of demonstrating higher education as an enabler, a social generator and an economic revitalizer in a depressed area.

Price subsequently developed his theories in published writings and projects, buildings, teaching and in stimulating lectures. He influenced a generation of architects (Richard Rogers acknowledged the Centre Georges Pompidou’s indebtedness to the Fun Palace) and helped to prepare the way for High Tech. For Price himself, however, the choice between ‘low’ or ‘high’ technology was one that had to be made on the basis of appropriateness. In 1976 Price carried his studies in supportive technology into the realm of artificial intelligence. His Generator project (unbuilt) proposed an intelligent building, a computerized leisure facility, which not only could be formed and reformed but, through its interaction with users, could learn, remember and develop an intelligent awareness of their needs.

Price’s anti-stylistic stance was consistently inventive, playful and informed with a technological and scientific awareness; but underlying all his work was an insistence upon the architect’s obligation to go beyond inventiveness and creativity. It was his view that architecture has to provide purpose, moral support, aesthetic enhancement and delight, even if no building can be expected to do this for very long, given the temporality of architecture.

Royston Landau

From Grove Art Online

© 2007 Oxford University Press

Aside: Returning to nets and structures, I also recalled landborne – or airborne – netted architecture, in the slightly more benevolent form of Cedric Price's aviary at London Zoo. I seem to remember that in Price's original idea, the aviary was mobile, able to move under the collective command of the birds. A self-aware flock, flying in one direction, would strain at the nets along one edge of the structure, slowly dragging it through the zoo. Or did I make that up?

Of course, it is possible to build complex, labyrinthine interior-orientated structures without it leading inexorably to a chamber of death. Desirable, even. On Arabic urban planning, note for instance that Koolhaas and Foster have both been drawing from this deep well recently. But perhaps the most interesting thing I've read about the Western focus on the exterior, at the expense of the essentially more important interior, is in Johani Pallasmaa's supreme book 'The Eyes of the Skin'. In this context, it's not only interesting that Pallasmaa describes "the haptic city" as one of "interiority and nearness", but that he illustrates this with a photo of the hill town of Casares, southern Spain, which is – of course – built to a Moorish plan. For Robb in Racalmuto, the town plan constricts and entraps, though perhaps the surrounding context of Cosa Nostra and the unified Italy's slow murder of the Mezzogiorno is as much to blame as the immediate warren of streets. Elsewhere, reading Robb suggests an affection for, and affinity with, the tightly bound streets and dark crevices of Naples and Palermo. In this, he is with Pallasmaa, for whom the chiaroscuro rendering and sinuous haptic presence of the traditional, pre-modern city plan provides a heightened sense of urban living and being, richly informed by memory, that can truly benefit the city and the citizen."

http://www.cityofsound.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment